Invasion ecology really opened my eyes to a whole new world. Studying how a species interacts with its living and nonliving environment is an extremely useful tool, especially in this human dominated era. We once intentionally transplanted species across continents without preconceiving how they would function. We now make predictions and carry out empirical studies to find out how non-native plants, animals and fungi can disrupt ecosystems outside of their home range. This change in mindset unfortunately was not a preemptive attempt to keep our lands ecologically pristine, but only occurred after the utter decimation of many native communities.

Long before the 1900’s, the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was the dominant tree of America’s East Coast. With one out of four trees in this expansive region being a chestnut tree, this plant played an imperative role, bearing huge, calorie filled nuts that many mammals and birds depended on. Chestnuts injected energy into the food chain which, back then was more species rich, supporting large predators like wolves and cougars. Our Eastern ecosystems were soon changed forever, when Asian chestnut trees carrying the fungal pathogen where brought to New York city in 1876. The first infected American chestnut was found in 1904 in the Bronx zoo, and by that time, it was probably already too late.

Pollen producing male flowers of the American chestnut, Castanea dentata.

n its native Asian range, the pathogenic Ascomycete fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) still infect the Asian chestnut trees. However, since the tree species have co-evolved alongside the fungus, they have developed defenses to reduce its detrimental effects. Evolutionarily speaking, without the American chestnut coming across a fungus like C. parasitica, it was just a matter of time until the tree met its match. This interaction involving species distribution has been coined novel weapons hypothesis, by Ragan M. Callaway in 2004. His hypothesis posits that, “novel weapons,” in this case the mechanism of fungal infection, is better suited to be used against naïve species that haven’t evolved genes to contest weapons from distant lands.

In his hallmark paper, Callaway describes that the Mongolian empire took over much of the old world with the invention of the recurved bow. Their opponents couldn't cope with the novel weapon, which led to the empire's dominance. Callaway 2004.

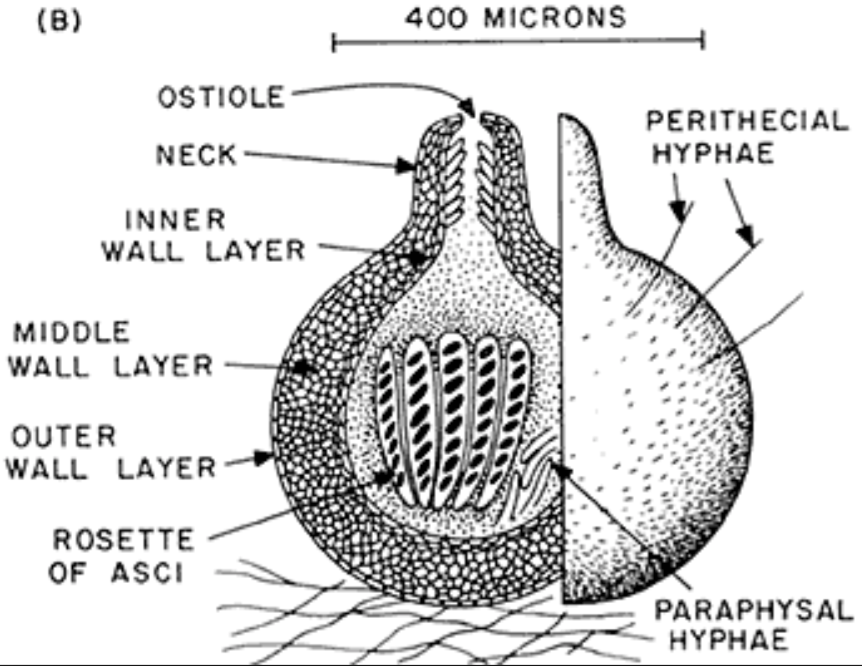

Once an infected Asian chestnut was brought to the States, sexual spores where ejected from perithecia into the air, and found their way onto suitable American chestnuts hosts. Spores that land on bark cracks or tree wounds germinate and grow beneath the bark. As it grows, the fungus essentially girdles the tree, cutting off its nutrient and water supply. With the tree’s health already compromised, asexual spores called conidia ooze out of fruit body structures called pycnidia. This orange ooze re-infects different parts of the already stressed tree, vectored by raindrops and animals that come in contact with it. When an all-out fungal infestation ensues, unsurprisingly, the American chestnut succumbs to the foreign invader.

Cross section of sexual spore producing perithecia.

Within just 40 years of the fungus making its way to our continent, nearly four billion American chestnuts were wiped out. There’s only a handful of disease resistant mature American chestnut left in the wild, but if you hike on the East Coast with attentiveness and purpose, you will encounter a ghost of the forest floors distant past. The blight can infect the aboveground tissues of its host no problem, but for whatever reason, the fungus cannot infect the chestnut roots. Some think that competition with soil microbes limit its infectivity, while others believe it’s just not adapted for an underground lifestyle. If you do frequent a place in nature that once held these woody giants, there’s a decent chance that a still living American chestnut root system has pushed a sprout up through the forest floor.

The Eastern giants before the fungal invasion. These trees once dominated our ecosystems. From Thompson 2012.

A young Leccinum sp. with shrub-like American chestnuts growing in the background. Picture taken in Chestnut Ridge Park, where the tree used to completely dominate.

I see these ecological shadows of the once massive trees all of the time while hiking through Western New York. These small, shrub-like American chestnuts with diameters no bigger than ten centimeters represent how an ecosystem that seems so sound can be transformed forever, with the introduction of a species that has not evolved there. Species that co-exist have a similar evolutionary trajectory, and adapt defenses to others offensives. Though, transplanting a pathogen or parasite with a separate evolutionary trajectory is like bringing a gun to a knife fight. These species bring a suite of novel weapons that native communities have never encountered. This goes to show that the forest floor is not a benevolent place by any means, but more of an ecological arms race. Some weapons like the ones within Cryphonectria parasitica have the ability to alter ecosystems on a colossal scale.