The myxomycetes are a unique group of organisms that were grouped together with fungi for hundreds of years. They produce small, fungal-like fruiting bodies that too release spores, but these species actually belong to the convoluted basal group of the animal kingdom; the protozoa. There are several unrelated lineages of protists, which is why zoologist have had a hard time categorizing them, even in the modern age with new, affordable genetic technologies. Many mycologists still study these organisms because of the similarities they share with other fungi. When I worked in my college’s herbarium, one of my summer jobs was to reorganize the fungal cabinets that haven’t been touched since the 80s. As you might know, fungal classification is an everchanging nightmare, and I soon realized I was in over my head. So much has changed in the world of mycology since the last fungal and slime mold specimens were cataloged in the herbarium. Although I was downright lost muddling through these dusty cigar boxes of preserved organisms that once inhabited the forest floor, I became infatuated with the preserved myxomycetes.

Looking at the different species of slime molds, this tiny world of the myxomycetes transported me to Alice’s wonderland. Even the herbarium specimens over 35 years old had a colorful, whimsical charm. Largely overlooked, these small organisms are more difficult to spot in nature, regardless of how vibrant they may appear under a dissecting scope. The specimens I looked at were just one stage of their lifecycle, the mature plasmodia. The mature plasmodia are made up of thousands upon thousands of individual cells. These mature plasmodia are analogous to the spore producing mushrooms of many fungi. Factors such as pH changes, as well as nutrient and resource availability trigger these single celled animal-like protozoa to congregate into these spore bearing structures. You really need a trained eye to spot them readily. They tend to grow on detritus like fallen logs, sticks, twigs, and leaves, and live in a diverse range of habitats, from the arctic tundra, to insanely hot and dry deserts. They consume bacteria, fungal spores and tissues, and other small particles of organic matter. Interestingly, just like fungi, there is the largest diversity of slime mold species at latitudes dominated by temperate ecosystems.

Diderma miniatum. Lado et. al 2019.

For nearly all the kingdoms of life on this planet, the most species rich areas occur near the equator. At 0˚ latitude, warm temperatures, the longest annual duration of sunlight, and ample water provide a wide range of plants with the main requirements for optimal growth. Through bottom up processes, the diversity and production of plant materials radiates up the food web which promotes the success of many other animal species. On the other hand, slime molds and fungi exemplify a different ecogeographical trend.

Fungal and slime mold diversity is highest near latitudes dominated by temperate forests. Shi et. al 2013.

There are several hypotheses that aim to describe this trend. Gilbert (2005) suggested that the insane plant diversity at lower latitudes sets the stage for less fungal specificity. For example, if there are just a few dominant trees growing in an area, there is a clear selection pressures for fungi to compete for those specific resources. Over evolutionary time scales, less specialization means lower species diversity. Another factor that drives these ecogeographical patterns amongst fungi and slime molds are the detritus-based food webs of the temperate forests. The seasonal influx of dead plant material each fall increases the resource load and niche spaces for these fungi and slime molds alike.

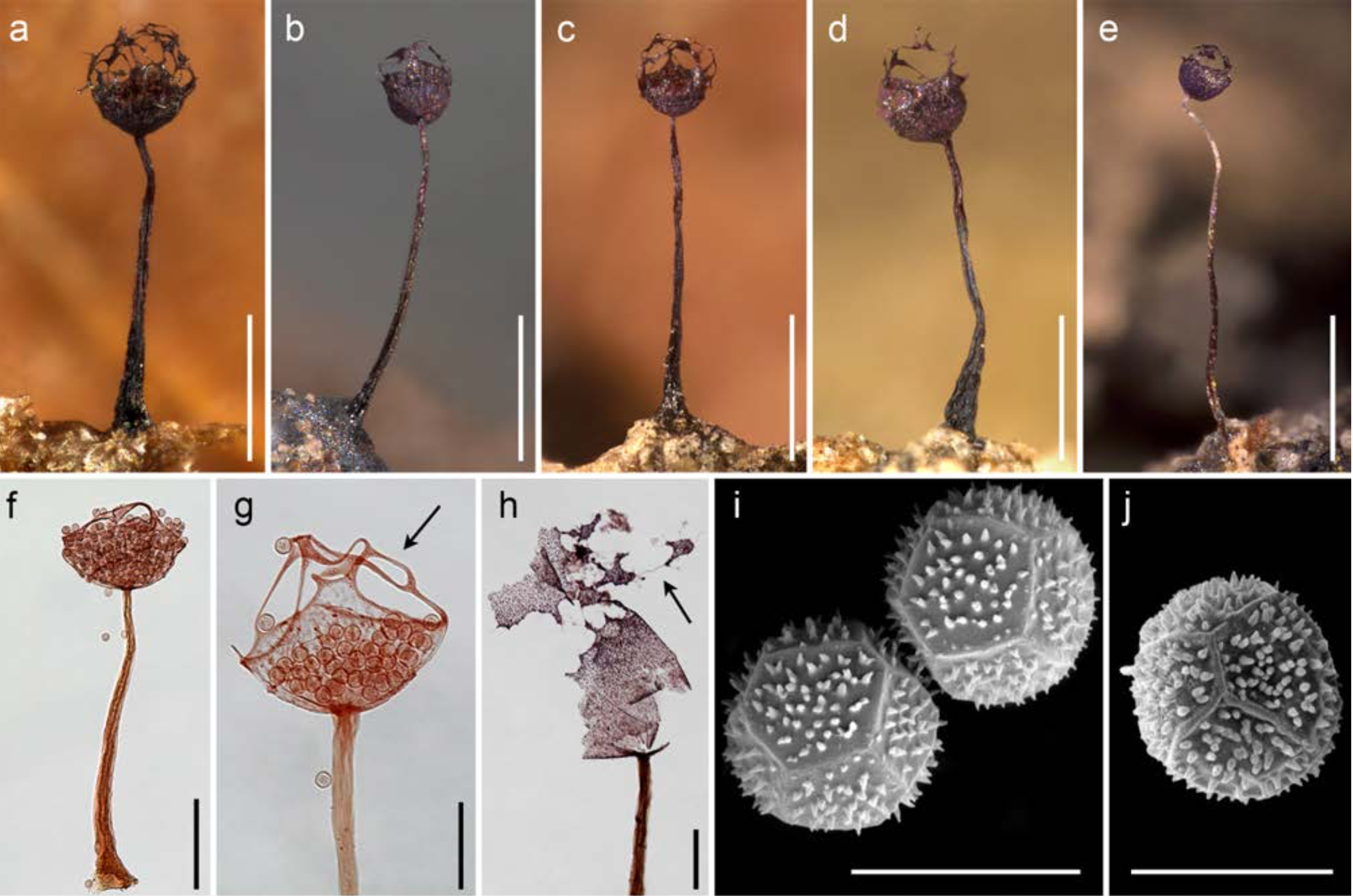

Diderma acanthosporum. Lado et. al 2019.

Again, slime molds like fungi occur in a diversity of habitats. A paper published recently cataloged the diversity of Myxomycetes species occurring in the most arid parts of Peru. Even in these cactus dominated ecosystems we find some ridiculously cool looking slime molds. Another paper published in 2008 highlighted a microhabitat for slime molds to flourish in tropical rainforests. Basanta et. al showed that long-stemmed, woody vine plants commonly known as lianas provide a productive substrate for myxomycetes in tropical rainforests.

Cribraria spinispora. Lado et. al 2019.

From deserts to tropical ecosystems, slime molds thrive by consuming other microorganisms and particulate matter. Luckily for me, since I live in a temperate area, there is a ridiculous diversity of fungi and slime molds around. I don’t have to travel far to find a temperate forest riddled with these species and slowly but surely, I am getting better at spotting these unique organisms that puzzled mycologists and zoologists for hundreds of years.