We really are just scratching the surface when it comes to describing fungal species. Every month, a handful of papers from all over the globe are published, that reveal new species of fungi. Newly described species are ordinary in the everchanging, dynamic field of mycology. Just back in February Xiao et al. described two new species of entomopathogenic cordyceps in Thailand.Ophiocordyceps globiceps and Ophiocordyceps sporangifera are the two new species of parasitic fungi that are similar in the fact that they infect and kill their insect host. They differ not only in their morphology, but in their host selectivity as well. In this week’s edition of Fungi Friday, I’d like to talk about these two newly described species, and discuss the importance parasites have in relation to ecosystem functioning.

Both Ophiocordyceps globiceps and Ophiocordyceps sporangifera were collected from tropical rainforests near Chiang Mai. Mature fruiting bodies of Ophiocordyceps globiceps are found growing from adult Dipteran flies, while the other closely related species, O. sporangifera specializes in parasitizing beetle larvae from the family Elateridae. These two species can live in such close proximity because of their different ecology. O. globiceps and O. sporangifera never compete, because they parasitize different insect species at different life stages. With nearly identical niche requirements, two very similar species can in fact inhabit the same ecosystem if they have evolved different feeding strategies. And interestingly enough, it is actually these very strategies that actually enhance forest biodiversity.

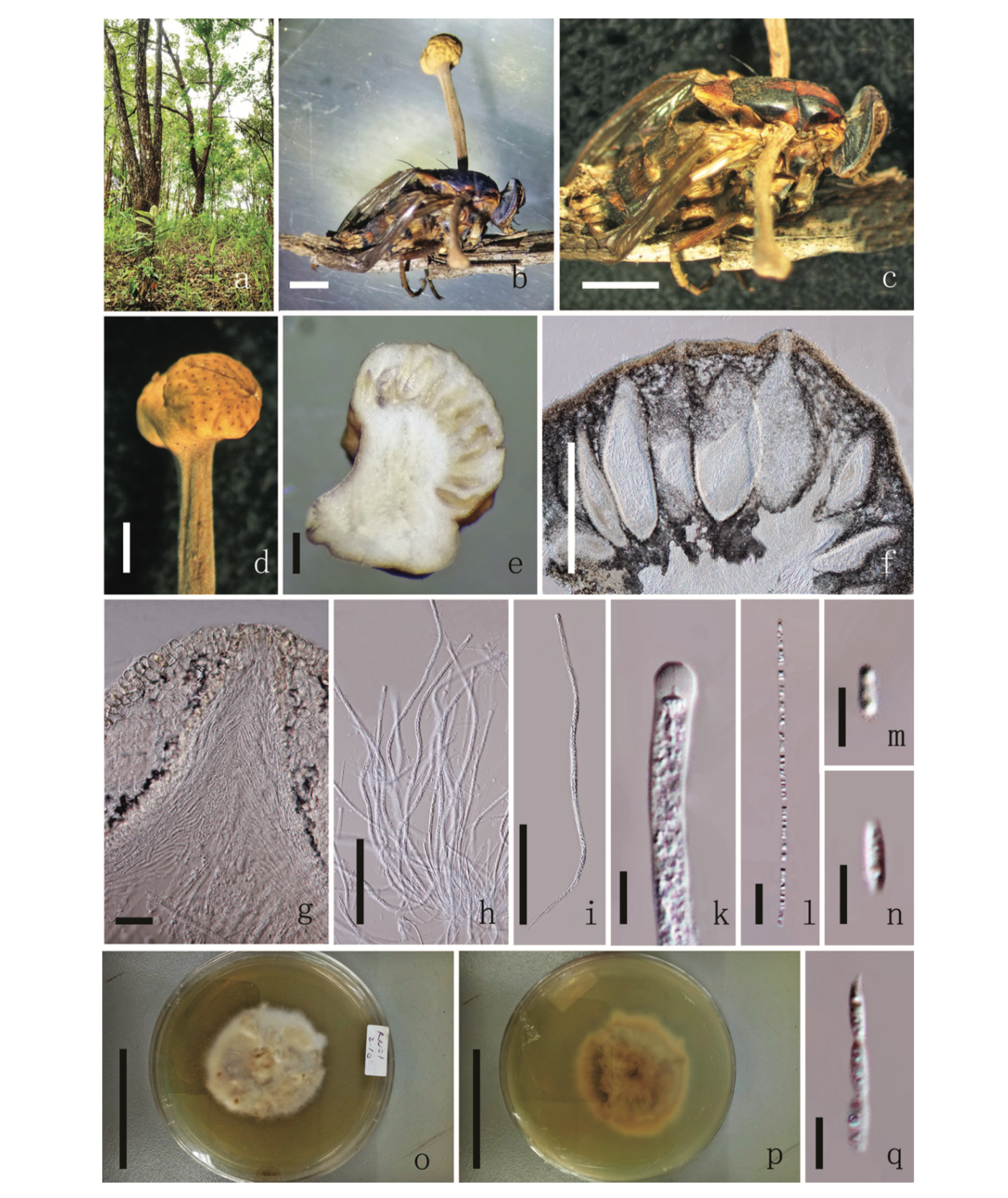

Ophiocordyceps sporangifera a Habitat b Synnemata on host surface c Host d, eSynnemata f Fertile head of primary synnema g Sporangium h Secondary synnema i Sporangium j, k, q Part of secondary synnema l Phialides m Conidia bound by deliquescing mucilaginous material n–p Conidia. Scale bars: 1 cm (c, d), 1000 µm (e), 200 µm (f, h, q), 100 µm (g, i), 50 µm (j), 20 µm (k, l), 10 µm (m–p). From Xiao et al. 2019.

In the mainstream, the word ‘parasite’ has a negative connotation that should revised. Trust me, it’s not your fault if you don’t know of the benefits parasitic fungi provide. The ecological roles parasites play has just recently been uncovered. Thirteen years ago, a review paper was published that highlighted the ecological importance of parasitic species. Peter Hudson, Andrew Dobson and Kevin Lafferty put together a comprehensive review about how these interactions relate to biodiversity.

It is no surprise that the healthiest, most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet also have the highest diversity of parasites. Now there is a stark difference in the interactions of generalist parasites vs. specialist parasites, as generalist parasites tend to decrease biodiversity. Overall however, many parasites tend to have a specialized ecology, parasitizing only a few species. Specialized parasites like O. globiceps and O. sporangifera do in factpromote biodiversity. There are several reasons specialized parasites promote species diversity.

Specialized parasites actually select for genetic diversity within a population. Genetic diversity enhances ecosystem stability, as populations with high genetic diversity will be more likely to resist a suite of ecological disturbances. Another parasitic interaction that enhances biodiversity has to do with trophic dynamics. O. sporangifera kills beetles from the family Elateridae. The majority of click beetles are herbivores, so by reducing plant feeding insects bottom up processes ensue. As primary productivity increases in areas with high abundance of O. sporangifera, other less dominate species of animals can feed and procreate. Simply put, plants freed from voracious herbivores photosynthesize more, and put more energy into the ecosystem. Forests with higher productivity can always support more biomass.

Zoomed in Dipteran fly parasitized by Ophiocordyceps globiceps . From Xiao et al. 2019.

New species always excite me not only because they have remained hidden from us for so long, but because of the way they interact with their surrounding ecosystems. In the rainforests of Thailand, Ophiocordyceps globiceps and Ophiocordyceps sporangifera enhance biodiversity. By parasitizing different insects, they can inhabit the same ecosystems. Specialized parasites around the world level the playing field, allowing less dominant organisms to gain an ecological foothold. Parasites that reduce voracious herbivores allow higher levels of primary productivity which ultimately leads to more energy entering the system. By altering bottom up processes through top down control, these newly described fungal parasites promote biodiversity.