The first time I ever encountered jelly fungus, I felt like I was exploring a distant planet and had discovered alien life. It didn’t look or feel like the polypores, boletes and agarics I was more familiar with, but I still had an inkling that, what I was looking at was in fact a species of fungus. I took the specimen home to study it more and hopefully identify it, but like most other jelly fungi, it was delicate, and basically melted into a brown-purple goop during the car ride home. I was reminded of my first encounter with a jelly fungus during a hike at Letchworth state park earlier this week, when I stumbled upon one of the most robust species of jelly fungi, Tremella foliacea.

Tremella foliacea, the leafy brain fungus.

Also aptly known as the leafy brain fungus, foliacea is a reference to the way the species resembles fallen foliage. Tremella foliacea like other species in the family Tremellaceae has quite an interesting life cycle. The fruiting bodies within the Tremellaceae release spores that germinate into single celled yeast fungi, unlike most other higher fungi that discharge spores that germinate into filamentous networks of hyphae. It isn't until the haploid single celled yeast stage of T. foliacea meets another compatible yeast cell, that they can combine and then can create a dikaryotic network of mycelia, in which each fungal cell in the hyphal strands contain two separate nuclei from the original two yeast cells. The dikaryotic network still needs to locate suitable substrate to acquire nutrients.

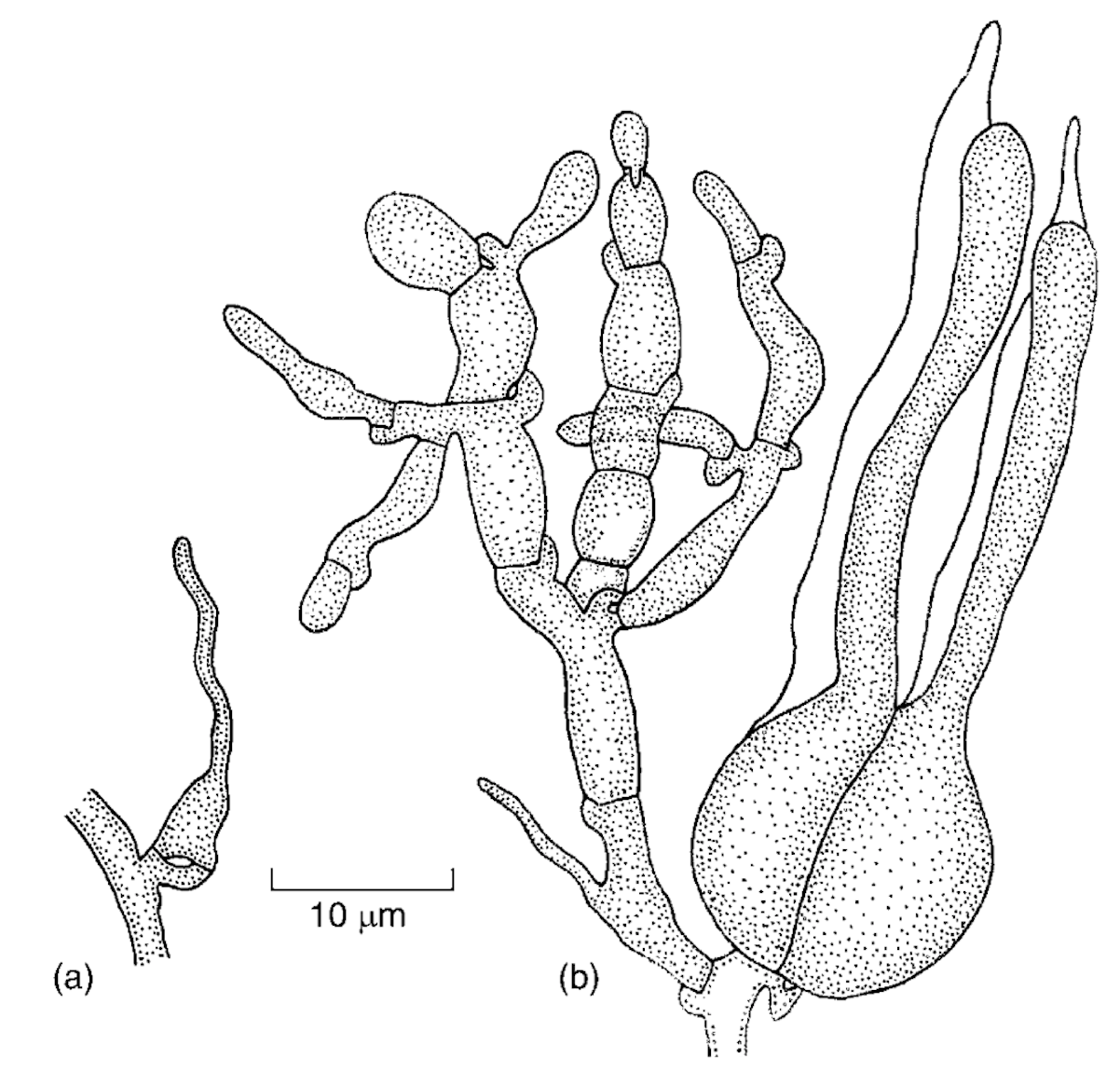

Interestingly, T. foliacea is actually a fungal parasite. Unlike other parasitic jelly fungi that parasitize the fruiting bodies of other fungi, T. foliacea parasitizes the hyphae of saprotrophic fungi. Through chemical signals released from wood decomposing fungi, the dikaryotic hyphae locate and grow towards the hyphae of Stereum species. Fungal structures called haustorial branches extend out and attach to hosts hyphae. Once attached, enzymes are released to break down its hosts cell wall, establishing direct contact with its cytoplasmic contents. It is only then that T. foliacea can steal carbohydrates and nutrients from the saprotrophic fungi.

Haustorial branches grow out of clamp connections (a) and attach to host mycelia.

Most of the time, this species is found on woody debris that is being broken down by Stereum species. But if you look at the pictures I took in this post, you will see the two fruiting bodies I found are fruiting from the forest floor. It might be parasitizing hyphae from saprotrophic fungi growing beneath the fungus, but some mycologists think that this species can carry out a saprotrophic lifestyle as well. Since this hypothesis surfaced, no evidence of enzymes strictly associated with the breakdown of woody debris has been isolated from the fungus.

Jelly fungi to the untrained eye may seem a bit alien. These organisms however did evolve on Earth and carry out several roles throughout Earth’s ecosystems. The ecology of T. foliacea is quite interesting, as it stealthily steals resources from other fungi that decompose wood. It is a possibility that this species was once mainly saprotrophic, and over recent millennia is making the switch to a more parasitic lifestyle. Remember, these evolutionary processes do not occur overnight, and the traits associated with a species past ecological function may be conserved for hundreds of thousands of years-even after it has evolved an alternate method to acquire nutrients.